|

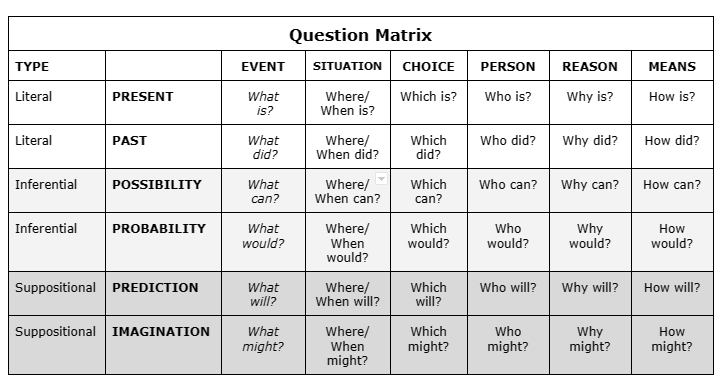

When teachers deliberately and intentionally insert questioning into a lesson, good things happen and when they teach students how to maximize questioning, nothing can stop them! Post and/or provide a copy of the matrix, train them how to use it effectively and watch them grow! QUESTION MATRIX (Questioning, Writing) Description: Developed by Chuck Weiderhold, the Question Matrix (Q-Matrix) is a set of question starters designed to recognize and develop higher-order thinking. It covers literal, inferential, and extended suppositional question formats. Application: The matrix can be used by teachers to ask a variety of questions. It can also be used by students to develop and broaden their metacognitive skills by being deliberate in asking what they need to know. Process: After direct instruction, review material with students and challenge them to create a number of questions based on the information. Introduce the Q-Matrix providing examples from the literal, inferential, suppositional formats. Project the matrix and allow students time to develop questions. Randomly call on students to share their questions, allowing other students to answer. Ask students to identify the type of questions asked (literal inferential, suppositional) and clarify if there are discrepancies between the answers. Resources and more information:

Weiderhold, C. (1991) The Question Matrix. edcr3332015thinkingmaps.weebly.com/question-matrix.html

0 Comments

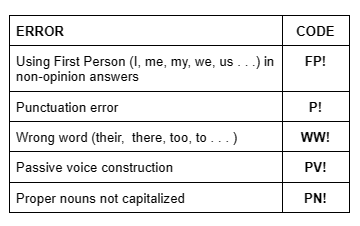

This protocol/strategy asks educators from all subjects that require the written word to allow students to be accountable for content as well as how the content is expressed. By selecting the five most glaring Language Arts mistakes within written responses and efficiently sharing that information with students can help them be mindful in all subjects, not just Language Arts. The key for teachers is to create a simplified marking code. Questions? Comment below. SIMPLIFIED CODED MARKING (Feedback, Writing) Description: Language Arts teachers have been using corrective feedback shorthand forever, but the practice in other subjects is rarely used and yet, many subjects require written answers. Subject-area teachers are focused on the content of the answer, but with one-time preparation, they can also require students to use fundamental mechanics, grammar, and format. This cross-connection firmly solidifies the idea that proper use of the written word spans all subjects, not just Language Arts. Subject teachers can point out glaring errors by using a simplified coded marking chart. Application: Use the simplified coded marking chart in any non-Language Arts subject that requires written work like short answer responses, reports, or subject matter essays. Process: Consult with other subject teachers in the school (optional) to create a uniform coded marking chart and create the document with the top five major errors students make in their written responses. Hand-out/post chart, review, and remind students to keep it for the duration of the class. Assign minimal point values to the errors and deduct from the overall assignment total. Reassure students that as errors are corrected, grades will rise. Because each group is different, use the example chart below as a template: For resources or more information:

Fairlamb, A (2018) Adventures in Coded Marking Adventures in coded marking (innovatemyschool.com) This technique was developed when my school hosted three-day teacher workshops. I also used it in my classes with great success and with just a little prep, it can save precious time and energy on the day needed. The other benefit is that students feel a sense of confidence because they know where to go and what to do when the teacher calls for groups to form. Efficiency is the name of the game! What do you do that makes grouping more efficient?

GROUP DYNAMICS (Collaboration) Description: Deliberate and intentional structured groupings created ahead of time will take the drudgery out of forming groups on the fly. Application: Use in all subjects and class formats, including online classes. Process: For the first week or two of class, observe students and look for things like traits, habits, and personalities. Make mental notes of who would work well together in partnerships, trios, and groups of four. Assign partnerships designated by numbers, trios by letter, and groups of four by city name. Create a sticker for each student that has their name and the unique code (Example: Jasmine Smith: 6-C-Omaha). Record the groupings in case a student loses the sticker. Tell students to put the sticker in the front of their notebook for easy reference. Show students the process by allowing them to meet their partners, trios, and groups of four. Begin by saying, “Find your matching number.” Partnerships form (assign only two of each number). Once students have met their partners, say, “Find your matching letters and trios form (assign only three students per letter), and say, “Find your matching city and groups of four forms (assign only four students per city). Be ready for noise the first time as students search for their groups. On class day when groups are needed, announce which code (number, letter, city) students use to find their group. Refer back to the sticker if a student forgets. Proceed with the activity once groups are formed. Modify as necessary. This protocol provides students a way to judge the quality of their work. Whether it is comparing shown work in similar math problems, reviewing mapping skills, or writing an essay, the strategy below will provide students with feedback to improve performance. How can you incorporate Choose-Swap-Choose in your classroom? Leave a comment below-

CHOOSE-SWAP-CHOOSE (Feedback, Discussion, Collaboration) Description: Because not everything can be or should be graded, Choose-Swap-Choose provides students with real time peer feedback focused on the quality of their work by analyzing, discerning, and eventually discussing with peers the most successful product from several iterations of the same or similar items. Application: Use this strategy in all subjects when measurement of progress or improvement is desired. Process: Refer to Model of Excellence's Attributes of High Quality Work to set standards. Provide students with an overview and relevant examples of quality before starting process. Be intentional by announcing which items students should keep/save because depending on what items are to be examined, the collection time can be within a class period, days, weeks, or months. At the appropriate time, list the items students will need for the activity and give them a few minutes to collect their work. Display at least three attributes of “quality” and ask students to review their work based on the attributes and decide which of the work exemplifies “quality.” Remind students to make a note of which item they chose. Once completed, students will swap their papers with a partner and based on the criteria, will select which work exemplifies quality. Provide time for students to defend choices and let the originator of the work make the final decision. Allow time for whole class discussion, focus on the listed quality attributes. Resources and For More information: Attributes of High Quality Work. Models of Excellence, The Center for High Quality Student Work. Attributes of High Quality Work | Models of Excellence (eleducation.org) Collin, J. Quigley, A. Teacher Feedback to Improve Pupil Learning Guidance Report. Education Endowment Foundation Choose Swap Choose Strategy (Meenakshi Narula - Mentoring The Mentors) https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/eef-guidance-reports/feedback/Teacher_Feedback_to_Improve_Pupil_Learning.pdf It's not easy to get students in the mood to be creative and write, but that is what this month's protocol is all about, creativity and mindset. Often times, students will engage in an activity because it is different, and they are curious, or the teacher provides enough structure and encouragement to get them started. Either way, this blog post is here to help! Please tell me in the comments what you do to get student's creative juices flowing.

JUMPSTART CREATIVE WRITING ACTIVITIES (Writing, Reading, Discussion) Description: Based on Barrie Davenport’s 11 Creative Writing Exercises That Will Improve Your Skills, these protocols allow students to concentrate on the content rather than the process of creative writing. Application: These activities are best used in subjects where reading and writing are standard practices. Process: Provide context when implementing these activities: 1. Everyone has an “inner author” ready to share experiences, knowledge, or stories, but it’s hard to get started. 2. The more one writes, the better at writing one becomes. 3. Writing should be without mind barriers like what others think of the writing or being a self-critic. Activity 1: Answer Three Questions: Create three questions to stimulate creative thought. Direct students to answer the questions quickly and write whatever ideas pop into their minds. Example: “Who just snuck out the back window? What were they carrying? Where were they going? or Whose house is Julia leaving? Why was she there? Where is she going now? From the answers, instruct students to create a written work based on the three answered questions and the five elements of a short story: character(s), setting, plot, conflict, and resolution. Activity 2: Write A Story Told To You: Remind students that they are retelling an event or experience from the past told to them and that the goal is to entertain, inform, and/or evaluate a situation. Provide structure: In the introductory paragraph, establish the setting and introduce the characters and the topic of the story. In paragraphs two, three, and four, relate the events in chronological order. In the final paragraph of the retold story, make an evaluative comment that provides closure to the recounted story. Activity 3: Pretend To Be Someone Else: Tell students to write from the perspective of a person known or an imagined character. Suggest students select a setting, situation, event, or encounter that exemplifies the person by relating what he/she is thinking, seeing, hearing, and feeling about the scenario. Outline length parameters, one paragraph to one page. Example: You are the English teacher when the fire alarm goes off during a test. Resources and for more information: Davenport, B (2022) 11 Creative Writing Exercises To Awaken Your Inner Author https://authority.pub/creative-writing-exercises/ How to Write a Recount Text (And Improve your Writing Skills). www.literacyideas.com We can hope that students work on exam reviews at home or come to after school exam review sessions, but sadly, hope is not a plan. By slightly adjusting our mindset, we can make sure that students are working by hosting in-class exam reviews. The benefits are endless, check it out and let me know what you think:

IN-CLASS EXAM REVIEWS (Feedback, Discussion, Collaboration, Writing) Description: Too often, teachers hand-out review items and expect students to complete them at home and unless the teacher goes over the review, there may be incorrect answers lurking. In this simple, but meaningful strategy, teachers provide time for students to work on reviews in class, with conditions. This approach also builds trust and camaraderie with students. It also guarantees that all students have been exposed to the material to be tested and some students actually learn the material while reviewing! And as an added benefit, it can satisfy some I.E.P requirements. Application: The In-class Exam Review process can be used in any subject. Process: Gather exam review documents, either paper or online in a file format. As exam time nears, explain to students that time will be set aside for exam review at each class meeting and to have review items at the ready. On the first day of the review, hand-out review items bundled in a stapled “packet” or release the online document’s file. Provide guidelines:

After an appropriate amount of time has passed, go over answers in a brief manner, but clarify misunderstandings. Optional approach, assign the next review as homework to encourage students to “see what they know” before the review. Tell them to make note of any question/answers that they did not know or made an educated guess and concentrate on those for the in-class review session. Resources and for more information: King, T. Rentz, J. (2022) “Teaching More and Talking Less: Using Examples During Class” Faculty Focus Podcast #35 The art of questioning is present in this protocol. Comment below and let us know if you do something similar in your class. FUNNEL QUESTIONING TECHNIQUE (Questioning, Discussion, Feedback) Description: Originally used in business, the Funnel Questioning Technique provides teachers with structure by improving the way they ask questions, figuratively resembling a funnel, broad to narrow. It mandates that different types of questions are asked in a particular order. Not only does the technique address academic concerns but can be used as a way to show genuine concern for students. Adapted heavily from Revolution Learning's The Questioning Funnel – Effective Questioning. Application: Apply the technique when evaluating students’ levels of understanding, seeking additional information, or enhancing relationships within the classroom. Process: Have a topic, lesson, or unit in mind when creating funnel questions. Review the general technique’s order: “...start with broad open questions, probe to gather more specifics, and then use a closed question to clarify.” Begin with open questions, examples include Who? What? When? Where? Why? Tell, Explain, and Describe. After a variety of student responses, initiate probing questions, also open-ended, that ask for more specific information. Make sure the “next” probing question is always based on the “last ''answer given, digging deeper each question/answer set. After probing, show students understanding by asking closed (yes/no) questions that confirm their answers. Examples of closed questions are Did? Can? Will? Are? If? Were? Is? etc. Provide ways such as summarization or short-answer response for students to encapsulate what they have learned through the process. Resources and for more information: The Questioning Funnel - Effective Questioning - Revolution Learning and Development Ltd A few years ago I read an intriguing article on "Exam Debriefs" by Maryellen Weimer, PhD in the online magazine Faculty Focus. Dr. Weimer challenges instructors to make testing a learning opportunity instead of just an entry in the grade book. This is innovation at its finest. Traditionally, teachers will "go over" answers from a test/exam, either in total or only the answers missed. (How tedious it must be for the student to review things she answered correctly!) While some may have questions about the implementation; for example, how to grade both quickly and efficiently or how to keep students from cheating, the notion that learning can happen from an unlikely source (exams and tests) has merit. Originally posted in 2016. Give it a try and let us know how it goes.

DOUBLE-TAKE TEST (Feedback, Writing) Description: Based on an article by Maryellen Weimer, PhD, a Double-Take Test allows students to correct their own tests giving them opportunities to learn material missed during study or to clear up any misunderstandings of the content. It can also be used as a measuring stick for the effectiveness of a student’s study methods. Application: Use this two-stage testing method for multiple-choice tests in any subject. Process: Create a multiple-choice test with a separate answer sheet. Before administering the test, decide corrections format. (Will students make corrections independently or in a group, during class time or at home?) Review the guidelines with students: 1) Read question, review answer choices, select best answer, and mark answer on both test book and answer sheet; 2) at completion, submit answer sheet and keep test book; and 3) follow format instructions and review answers in book, make corrections, and submit next class meeting. Score both test book and answer sheet awarding two points if answers to question are correct on both, one point if answer was correct on one but not the other, and no points if answers to question are incorrect on both. (If cheating is a concern, avoid “at home” corrections and provide time the next class meeting for students to make corrections.) Weimer, Maryellen (October 19, 2016) http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/getting-exam-debriefs |

AuthorAlison Thetford, M.Ed CategoriesPast Posts

March 2024

|